I live in a country that I have known and loved for more than half of my life. I feel part of its living, breathing fabric and it’s an indelible part of who I am. Building on my vestigial instincts, England is what made me the bleeding-heart, doubting, tormented cosmopolitan I feel that I am meant to be. Slowly but surely, it rubbed away most signs of who I was before I knew it. I belong here, it is my home.

I live in a country that I have known and loved for more than half of my life. I feel part of its living, breathing fabric and it’s an indelible part of who I am. Building on my vestigial instincts, England is what made me the bleeding-heart, doubting, tormented cosmopolitan I feel that I am meant to be. Slowly but surely, it rubbed away most signs of who I was before I knew it. I belong here, it is my home.

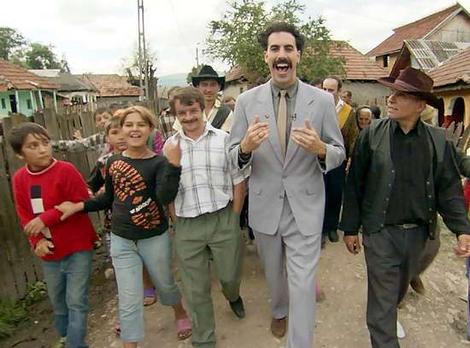

Lately, our government has been working hard to raise alert about the impending invasion of my countrymen, rebranded bogeymen. Romania and Bulgaria’s seven-year “transitionary” restrictions to the EU labour market are coming to an end, which in theory should make all EU citizens equal. We are told they are poised to invade these fragile shores and pilfer our lowest-status jobs, seduce our women, and push in front of us in the queue at Sainsbury’s. Or something like that. We don’t know how many will turn up and what untold chaos they will wreak, but we await them nervously. The appalling barbarians must be dissuaded from believing they will have a fun time in these parts, so we are making TV adverts assuring them they won’t. In their grotesque lack of sophistication, they will think twice about moving to a country where it rains a lot and where they won’t find a ‘welcome’ dole office at the border so that they can take advantage the second they arrive.

Inconvenient truths must be cast aside to protect the nation – such as that migrants have been shown to be substantially less inclined to claim benefits than their bona fide British brothers and sisters.

I for one didn’t turn up on these shores for the weather nor for the legendary 60 pounds per week of Jobseekers’ Allowance. I wasn’t terribly interested in reaping the benefits of Western neoliberal capitalism either. I came to the UK because I felt at home among its self-deprecating, open-minded and reflective people. In time, I grew accustomed to unyielding gravity-fed hot water systems, mint sauce and harassment at the border control desk. It was a price I could happily pay to live in a society of like-minded folk. I am now told I was miss-seeing things. England didn’t mean it. We are not all born equal. My presence is worrisome. England had rather I stopped playing with its toys.

The incensed are right to a large degree. Their innate sense of fairness is quite rightly ringing alarm bells. Some people out there are indeed taking advantage. They are stoking up our basest fearful instincts, hopeful that we might overlook the real abuses they themselves are carrying out. Frothing with rage at the thought of – largely imaginary – outsiders benefiting unduly from a society they do not contribute to, we close our eyes to those robbing us blind from their privileged positions near the centre of power. It is the dismantling of the public service system and its selling off to a variety of friendly bidders that should make us angry, and the demonization of the state in its protective – but never its coercive – capacity. It’s the dissolution of our employment and social security rights that should incense us. These are the things making life much worse for us and those who will come after us. Not the Eastern European bogeyman.

Prone still to a rather Romanian penchant for drama and overreaction, I half-expect to be escorted off the island.